Push Is On in US to Figure Out South Asians’ High Heart Risks

For years, Sharad Acharya’s frequent hikes in the mountains outside Denver would leave him short of breath. But a real wake-up call came three years ago when he suddenly struggled to breathe while walking through an airport.

An electrocardiogram revealed that Acharya, a Nepali American from Broomfield, Colorado, had an irregular heartbeat on top of the high blood pressure he already knew about. He had to immediately undergo triple bypass surgery and get seven stents.

Acharya, now 54, thought of his late father and his many uncles who have had heart problems.

“It’s part of my genetics, for sure,” he said.

South Asian Americans — people with roots in Nepal, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Bhutan and the Maldives — have a disproportionately higher risk of heart disease and other cardiovascular ailments. Worldwide, South Asians account for 60% of all heart disease cases, even though — at 2 billion people — they make up only a quarter of the planet’s population.

In the United States, there’s increasing attention on these risks for Americans of South Asian descent, a growing population of about 5.4 million. Health care professionals attribute the problem to a mix of genetic, cultural and lifestyle influences — but researchers are advocating for more resources to fully understand it.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) is sponsoring legislation that would direct $5 million over the next five years toward research into heart disease among South Asian Americans and raising awareness of the issue. The bill passed the U.S. House in September and is up for consideration in the Senate.

The issue could gain more attention after Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) becomes the nation’s first vice president with South Asian lineage. Harris’ mother, Shyamala Gopalan, moved from India to the U.S. in 1958 to attend graduate school. Gopalan, a breast cancer researcher, died in 2009 of colon cancer.

A 2018 study for the American Heart Association found South Asian Americans are more likely to die of coronary heart disease than other Asian Americans and non-Hispanic white Americans. The study pointed to their high incidences of diabetes and prediabetes as risk factors, as well as high waist-to-hip ratios. People of South Asian descent have a higher tendency to gain visceral fat in the abdomen, which is associated with insulin resistance. They also were found to be less physically active than other ethnic groups in the U.S.

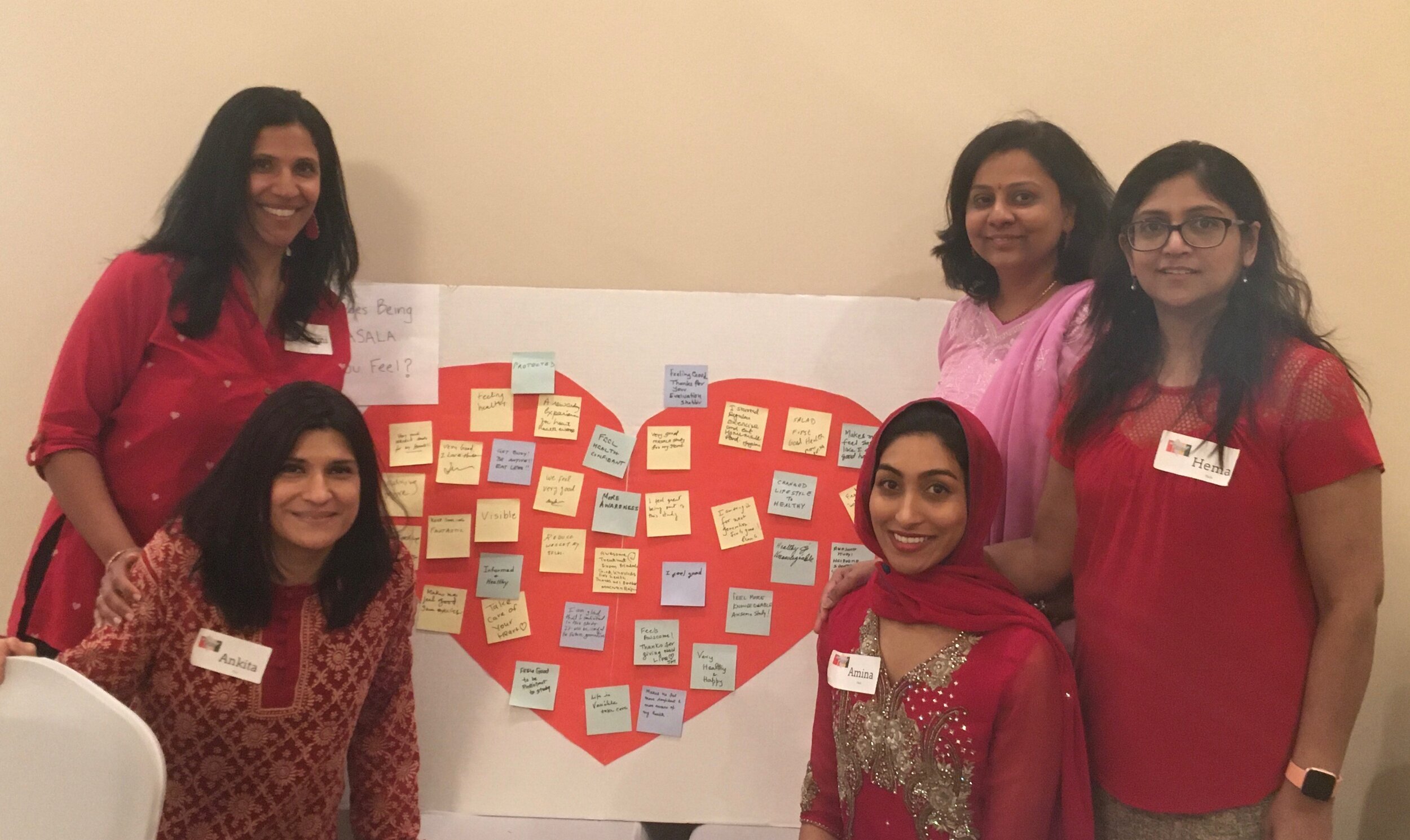

One of the nation’s largest undertakings to understand these risks is the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America study, which began in 2006. The MASALA researchers, from institutions such as Northwestern University and the University of California-San Francisco, have examined more than 1,100 South Asian American men and women ages 40-79 to better understand the prevalence and outcomes of cardiovascular disease. They stress that high blood pressure and diabetes are common in the community, even for people at normal weights.

That’s why, said Dr. Alka Kanaya, MASALA’s principal investigator and a professor at UCSF, South Asians cannot rely on traditional body mass index metrics, because BMI numbers considered normal could provide false reassurance to those who might still be at risk.

Kanaya recommends cardiac CT scans, which she said help identify high-risk patients, those who need to make more aggressive lifestyle changes and those who may need preventive medication.

Another risk factor, this one cultural, is diet. Some South Asian Americans are vegetarians, though it’s often a grain-heavy diet reliant on rice and flatbread. The AHA study found risks in such diets, which are high in refined carbohydrates and saturated fat.

“We have to understand the cultural nuances [with] an Indian vegetarian diet,” said Dr. Ronesh Sinha, author of “The South Asian Health Solution” and an internal medicine physician. “That means something totally different than … a Westerner who’s going to be consuming a lot of plant-based protein and tofu, eating lots of salads and things that typical South Asians don’t.”

But getting South Asians to change their eating habits can be challenging, because their culture expresses hospitality and love through food, according to Arnab Mukherjea, an associate professor of health sciences at California State University-East Bay. “One of the things South Asians tend to take a lot of pride in is transmitting cultural values and norms knowledge to the next generation,” Mukherjea said.

The intergenerational transmission goes both ways, according to MASALA researchers. Adult, second-generation South Asian Americans might be the key to helping those in the first generation who are resistant to change adopt healthier habits, according to Kanaya.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, El Camino Hospital’s South Asian Heart Center is one of the nation’s leading centers for educating the community. Its three locations are not far from Silicon Valley tech giants, which employ many South Asian Americans.

The center’s medical director, Dr. César Molina, said the center treats many relatively young patients of South Asian descent without typical risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

“It was like the typical 44-year-old engineer with a spouse and two kids showing up with a heart attack,” he said.

The South Asian Health Center helps patients make lifestyle changes through meditation, exercise, diet and sleep. The nearby Palo Alto Medical Foundation’s Prevention and Awareness for South Asians program and the Stanford South Asian Translational Heart Initiative provide medical support for the community. Even patients in the later stages of heart disease can be helped by lifestyle changes, Sinha said.

Dr. Kevin Shah, a University of Utah cardiologist who co-authored the AHA study, said people with diabetes, hypertension and obesity are also at higher risk of COVID-19 complications so should now especially work to improve their cardiovascular health and fitness.

In Colorado, Acharya’s health is still an issue. He said he had to get four more stents this year, and the surgeries have put pressure on his family. But he’s breathing well, watching what he eats — and once more exploring his beloved mountains.

“Nowadays, I feel very, very good,” he said. “I’m hiking a lot.”

Subscribe to KHN's free Morning Briefing.